Oh, to be a general!

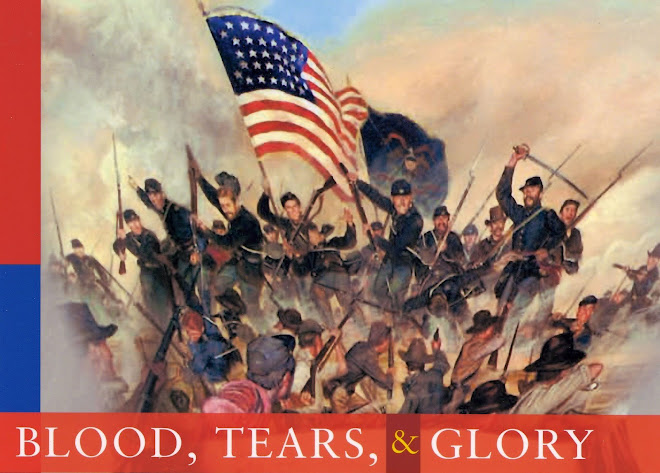

Many a Civil War-era lad fell asleep to dream of becoming the heroic commander of a great army. Popular lithographs by Currier & Ives and other publishers pictured warfare in an impossibly romantic way. Under blue skies with only an occasional fleecy cloud, neat rows of soldiers fired at each other on an impeccable landscape. Generals rode prancing white horses and did a lot of waving of swords. Only a few bodies, remarkably unbloodstained, could be seen lying on the grass, and sometimes the grass looked as if it had just been mowed. (Above: Gen. William S. Rosecrans, an Ohioan)

Balderdash.

Being a general in the Civil War was tough, dangerous work with very little job security. As the war went on, President Lincoln learned to not tolerate inaction or failure by commanders of the Army of the

There is also something innate in the nature of a general’s daily work, and that is tedium. Most of a general’s days are spent shuffling paperwork, administering discipline to recalcitrant underlings, and keeping the wheels of an enormous machine oiled.

On this weekday, Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, writes his sister, Mary, and (with original spelling retained) gives us a glimpse of his work life:

I wish you could be here for a day or two to see what I have to go through from breakfast until 12 O Clock at night, seven days a week. I have just got through with my mail for to-night, and as its is not yet 12 and the mail does not close until that time, I will devote the remainder of the time in pening you a few lines. I have no war news to communicate however.

Whilst I am writing several

Apparently, Grant was prompted to write this letter while trying simultaneously to entertain “several

Oh, to be a general!

Elsewhere in the Western Theater: From the 23rd

And in

The Big Picture: Except for some

No comments:

Post a Comment